Improving the AERO Recipe: Forging a True Partnership for Evidence-Informed Education

- Andy Mison

- Jul 17, 2025

- 4 min read

By Andy Mison, President, Australian Secondary Principals' Association

The establishment of the Australian Education Research Organisation (AERO) was a cautiously welcomed development for school leaders. A well-resourced, independent national body with a mandate to strengthen the use of evidence is something principals would see as useful. With a significant annual taxpayer investment of over $18 million, AERO has the potential to be a powerful partner in our collective mission to improve outcomes for every student.

However, as AERO’s work has rolled out, a level of concern has emerged from across the profession. While no one disputes the value of evidence, the critical question is: what counts as evidence?

Currently, the debate suggests AERO promotes a narrow, hierarchical view, privileging quantitative studies like randomised controlled trials.[1][2] While valid to an extent, this approach risks reducing the complex art and science of teaching to a set of technical, "what works" recipes.[3] It positions educators not as the adaptive experts they are, but as technicians expected to implement pre-determined strategies.[4] This top-down model feels disconnected from the dynamic and diverse contexts of our schools, where a "one-size-fits-all" solution rarely fits anyone perfectly.

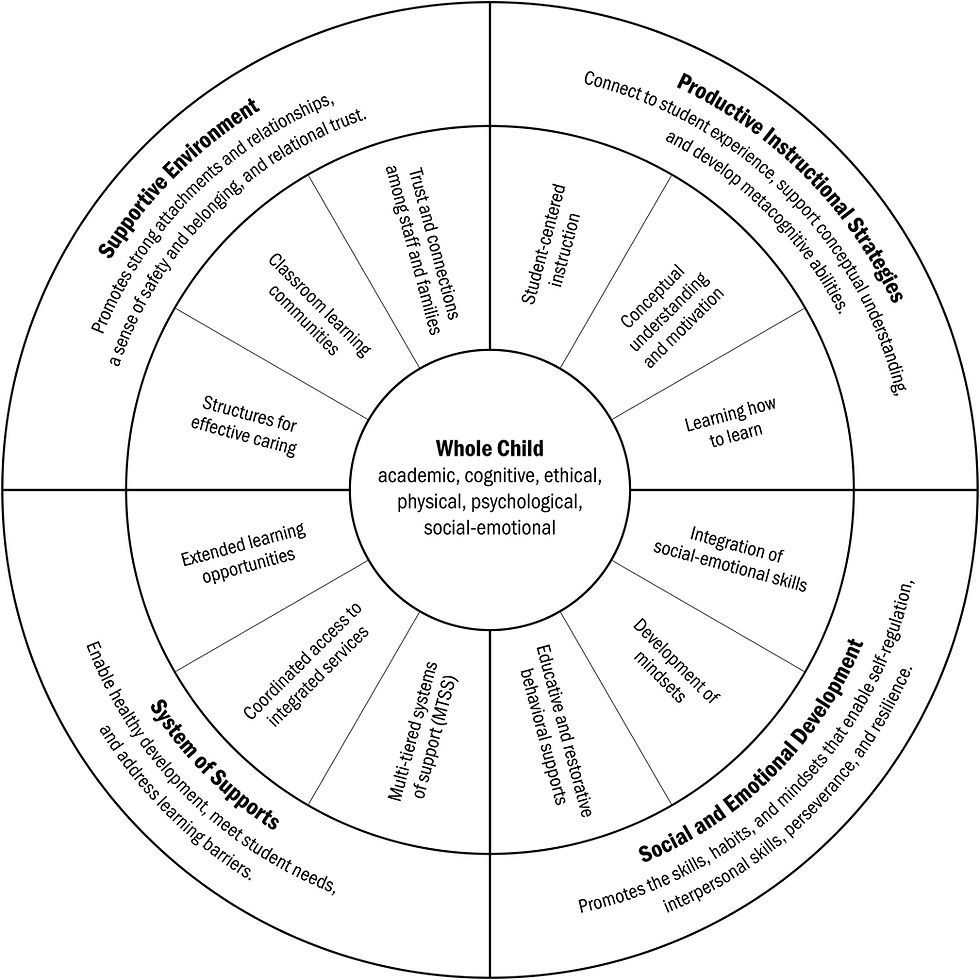

This narrow lens stands in contrast to the broader, more holistic understanding of effective practice described in the comprehensive research on the science of learning and development. Work by scholars like Linda Darling-Hammond and her colleagues synthesises evidence from multiple fields to paint a richer picture of how students learn best.[5][6] This framework shows that powerful learning happens in an integrated ecosystem that includes:

● Supportive environments built on strong, trusting relationships and a sense of safety and belonging.[5]

● Productive instructional strategies that connect to students' prior knowledge, foster deep conceptual understanding, and develop metacognition through inquiry and feedback, with a healthy dose of explicit instruction too![5]

● Intentional development of social and emotional skills, habits, and mindsets like resilience and agency.[5]

● Robust systems of support that address the needs of the whole child.[5]

This is the complex reality that school leaders and teachers navigate daily. It’s where concepts like a guaranteed and viable curriculum [12] become so powerful. This isn't a rigid, top-down script. It's a framework where school leaders and teachers exercise their collective professional judgment to identify the essential knowledge and skills all students must have the opportunity to learn (the 'guarantee'), and then ensure this core curriculum can realistically be taught in the time available (making it 'viable'). Crucially, this process respects their expertise in deciding what is most important for their students and how best to teach it, rather than imposing a one-size-fits-all solution from afar. This professional expertise—the ability to make these critical, context-specific judgments—is the most crucial form of evidence, yet it seems to be the one most undervalued in the current discourse.

This sense of being de-professionalised is occurring in a challenging climate. The narrative of systemic failure, often driven by a selective reading of international test results, is not fully supported by a holistic analysis of the data. As research by Dr. Sally Larsen shows, once you look beyond PISA to include NAPLAN, TIMSS, and PIRLS, the story is not one of broadscale decline, but of improvement in primary years and stability in secondary.[7][8]

Yet, this questionable narrative of decline has fuelled decades of top-down reforms and a narrowing focus on literacy and numeracy, often at the expense of the deeper, evidence-informed professional approach that we know works. Is it any wonder, then, that so many dedicated teachers and principals feel demoralised, overworked, and undervalued?[9][10] Recent surveys confirm that teacher morale and wellbeing are below optimal, a situation that undoubtedly exacerbates the teacher shortages we now face.[11]

AERO is a young organisation with a vital role to play, but to fulfil its promise, it must build trust and credibility with the profession it seeks to serve. This begins with broadening its conception of evidence to genuinely include the professional knowledge of teachers and leaders. The significant public investment in AERO demands accountability, and the best form of accountability is ensuring its work is seen as relevant, respectful, and useful in our schools.

Educators want to work in partnership with AERO. ASPA hopes to see the organisation evolve by giving school leaders and teachers a more significant role in how it designs its research and prioritises its output. A healthier move would be to build a shared understanding of the complex ingredients of great teaching and learning, rather than simply searching for recipes.

Our students deserve an education system that trusts and empowers its professionals to make the best decisions for their learning. By combining AERO's research capacity with the deep contextual expertise of educators, we can forge a true partnership that will genuinely lift our schools and create a more equitable and excellent education system for all.

Learn more:

Why AERO should take a long hard look at itself - EduResearch Matters

AERO says educators can trust its evidence. Can they really? - EduResearch Matters

Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development

Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development

Data defies picture of academic decline in Australian schools - University of New England (UNE)

Wellbeing strategies for principals to thrive in 2025 - The Educator Online

Students and teachers need better wellbeing support - Australian Education Union

.png)

Comments